Today has been Rabbie Burns Day, the 257th anniversary of the birth of Robert Burns, the poet. I did not have haggis (my wife can’t abide it), but I’m having a wee (or not-so-wee) dram of Scotch as I write this. I’m celebrating, but more about that anon. I’d like to toast dear Rabbie with a toast that was probably written after he was under the turf: Here’s tae us! Wha’s like us? Gey few, and they’re a’ deid!

This is best translated into standard English as “Here’s to us! Who’s like us? Damn few, and they’re all dead!” But gey does not mean ‘damn’. It means ‘very’ or ‘rather’ or ‘pretty’ (in the intensifier sense). Gey few means ‘rather few’ or ‘a good few’.

This is Scots, of which there is more than one variety. I don’t have any books on the Ayrshire dialect of which Burns was a native speaker (and anyway he was a native speaker of the 18th-century variety), but I happened to acquire an entertaining book on another dialect at some book sale or store or honestly I can’t even remember. It’s hiding on the top shelf of my dictionaries and phrase books.

It’s not very big; you can barely see it between the Czech and the Dutch. Here it is in my kitchen.

This is an entertaining, charming book, replete with cartoons. It is meant to be amusing, but it is at the same time accurate – it’s not taking the piss; it’s written by someone who grew up speaking the Doric dialect.

Doric, to me, always meant one of the orders of classical architecture. It was the one with the boring columns (Ionic had the curly capitals and Corinthian had the leaves). But this Doric is a dialect of Mid Northern (aka Northeastern) Scots. Here’s a Wikipedia article on it: https://sco.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doric. Oh, sorry, that’s in Scots. Try this one; it’s in English: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doric_dialect_%28Scotland%29. Anyway, if you’ve ever tried to understand someone from around Aberdeen, Doric is what you were up against. Scots is its own language, split off from English centuries ago, but as it is, because it looks somewhat recognizable to English speakers, we kid ourselves that we should be able to understand it, and some people still mistakenly believe that it’s just a regional variety of English. Well, Swedes and Danes understand each other, generally, sorta, and there’s about as much difference between Swedish and Danish as there is between Scots and English. The Doric dialect, as it happens, is named after the Greek area, apparently because the Scots were being compared to Spartans.

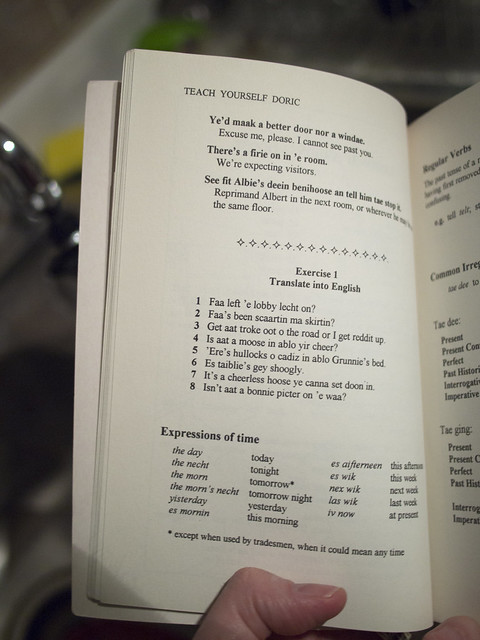

Here’s a page from that fun book:

At the top you see the end of a “Useful Phrases” section, including such as “Ye’d maak a better door nor a windae,” dryly translated as “Excuse me, please. I cannot see past you.” The translations assume you can figure out the literal translation (‘You’d make a better door than a window’, which is also a common phrase used by Canadians, usually addressed to school-aged youth who haven’t figured out where not to stand). But look a bit farther down the page and there’s this nice line:

Es taiblie’s gey shoogly. It means ‘This table is very wobbly.’ And so here is our word of the day, gey. Shoogly would be a good one too, but it can wait.

Whence comes gey? The Oxford English Dictionary is helpful on that, since the word is fairly widespread, not only in Scotland but also in Ireland and northern England. It comes from the same source as English gay – you could say it’s another version of the same word. English gay came into the language meaning ‘bright, brilliant, lively, showy’ and also from that ‘happy, light-hearted’. More than a century ago (just how long ago is unclear because it was surely used orally long before it showed up in the printed record) it came into use to refer to men preferentially attracted to other men, and that usage has become the supervenient one now, at least in part because so many people who aren’t homosexual avoid using it lest they be mistaken for such. The long history leading up to that usage is a whole other story that I’m not going to spend time on today just because gay isn’t the word of the day. Gey is. And gey went from a specific positive to a general intensifier (like very, originally ‘truthfully’; damn, short for damned and you damn well better know the literal meaning of that; and more modern colloquial usages such as wicked).

What was the source from which gay and gey came? French gai, which meant and still means ‘happy, cheerful’, and a variety of extended senses. The history before that is surprisingly complicated but apparently involves Old High German. Yes, even the Old High Germans could be happy. And the French of course know quite well how to be happy. The interjection o gai or just gai can be heard in some French folk songs such as “En montant la rivière” and even the Breton “Tri martolod.”

So, now. What cause have I to be happy and drink a toast today? Aside from good auld Rabbie, of course (and for more of him, spin back a few years to my vignette on skirl). My cause to be happy is just this: I have finished the first draft of a thesis. So let’s have some whisky already!

Speaking of things shoogly, have you come across the “acid craft” band Shooglenifty?

That would be Acid-Croft, not craft. As in “the original Acid-Croft, Hypno-folkadelic, Ambient Trad Band”, no less.

In Britain it’s still possible to drive three hours, and find locals speaking a dialect of English so different to yours it’s almost like another language.

Cheers to the thesis draft!

Oooops! Croft mutating into craft was down to iOS being officious. But I should have checked before posting!

Pingback: The Nitpicker’s Nook: February’s linguistic links roundup « BoldFace

Hi – I know this article is a few years old but Scots isn’t a dialect of English, it’s a separate language (in the view of the majority of linguists). Doric meanwhile is the North East dialect of Scots. Thanks for taking an interest in Scotland and it’s languages however! 🙂

Hi! Thank you for pointing this out—it’s something that I have since come to understand, and I had forgotten that I wrote incorrectly here. I’ll correct it now!

I come from a Border Riever family (the Littles) who occupied the Debatable Lands that straddled the 1273 border between Scotland and England. Some of my family came from Aspatria on the Solway plain. Today the people of Aspatria (population 2800) speak a true dialect (ie. not just an accent) and within the town there are at least three different ways of speaking the name of the town. My family favour Spee-a-tree. The Burns toast is made at every family gathering. The first I remember was in the late 1950s at my grandmother’s wake, (malt whisky to drink and Dundee cake made with blended whisky to eat).

As for Haggis, I make a traditional dish called Cumberland Tatie pot. (TayTee). It’s made in a single pot from mixed meats, root vegetables, and potatoes which are put in raw and so cook in the meat juices. Some people just keep adding whatever is to hand as the stew gets eaten. I have eaten from a tatie pot that was started more than a hundred years ago. The pot itself has been renewed three times in the life of the stew. Originally Tatie Pot had mutton and black pudding (blood sausage) in it. My own recipe has Venison (there is a glut of deer in UK at the moment and so it is cheaper than beef or English lamb) black pudding, cumberland sausage and haggis in it. My local butcher (The Black Pig in Deal – long may she live) makes Haggis sausages in proper sausage skins and these hold together nicely in the stew which I cook in a Slow Cooker though I deliberately burst the black pudding so that the squemish cannot identify it. I suppose I have served it to many hundreds of people. I never say what is in it apart from the potatoes of course. Guests often ask but it is easy to say “it’s a family secret” No one, except the vegetarians, has ever refused it. Most ask for a second helping. I know, without any evidence, that a significant proportion of our guests would say that they hate either haggis or black pudding or both.